By Anastaciya Pellicano, Jensen Horvath, Destiny McDaniel and Alisha Durosier

In December 2021, when Carlos Lovett was first asked about his experience growing up in St. Petersburg’s Gas Plant District, he was not expecting to be featured in a documentary.

While attending a cookout organized for former Gas Plant and Laurel Park neighborhood residents, Lovett recounted growing up with 10 older siblings in their house on First Avenue South. He could point to where his family’s home once stood from where he sat: parking lot number one of Tropicana Field, the former site of the Laurel Park residential complex.

“I just thought, okay, these people are going to go down there and talk and just commune together,” Lovett said. “I thought that was going to be it.”

Lovett is among the youngest of the Gas Plant residents to be featured in “Razed: Lies, Baseball, and the Price of Progress.”

Having premiered on Saturday, Feb. 22 at the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg, the documentary highlights the historical Black community that once flourished in St. Petersburg’s Gas Plant District. The community, which occupied 85-acres in the heart of downtown, was paved over to build the St. Petersburg ballpark, Tropicana Field.

Produced by Roundhouse Creative with support from other local foundations, “Razed” was directed by Andrew Lee and Tara Segall. Over the span of three years, Lee and Segall conducted interviews with 20 former Gas Plant residents and three local historians, capturing the neighborhood’s history from its inception to its eventual displacement.

“The film is in large part told through their voices,” Lee said.

Born on Tropicana Field’s parking lot one, the making of “Razed” started during a December 2021 cookout.

In collaboration with the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg, the African American Heritage Association, the Tampa Bay Rays and the city of St. Petersburg hosted the cookout and hired Roundhouse Creative to facilitate a video booth where residents were filmed speaking about their memories of the Gas Plant and Laurel Park neighborhoods.

Until then, Segall had never heard the words “Gas Plant Neighborhood.”

“Here I am in a community with somebody like Carlos, who has had this experience impact him so deeply and I don’t even know about it,” Segall said. “I think for Andrew and I, we felt upset by the fact that we didn’t know. But then also inspired by the opportunity to be able to share the story.”

Carl Lavender Jr., of the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg, alongside Lee and Segall, developed the idea to create a film about the Gas Plant District. However, Lavender emphasized that the film would not come to fruition without the approval or involvement of local historian, AAHA president and former Gas Plant resident, Gwendolyn Reese. This guided Lee and Segall’s decision to bring Reese on as a producer.

“My role as producer … was primarily identifying people who lived in the Gas Plant Neighborhood and reaching out to them because they knew me,” Reese said. “They didn’t know Roundhouse Creative.”

In the documentary, what is seen are not formal interviews with the locals, but rather a discussion between them and Reese, who sat out of the camera’s view and facilitated a conversation.

In cutting down over 30 hours of footage into a 75-minute film, Lee and Segall wanted to make sure the documentary was balanced.

“It’s equal parts, I think, making sure that we convey the joy and the connectivity and the love that was there,” Lee said. “And then also telling the story of what happened… and how that changed.”

According to Reese, the story of the Gas Plant District is multifaceted.

“Our story is like any other story,” she said. “It has its dark sides, but it has its joyous and light sides. We want people to know all sides.”

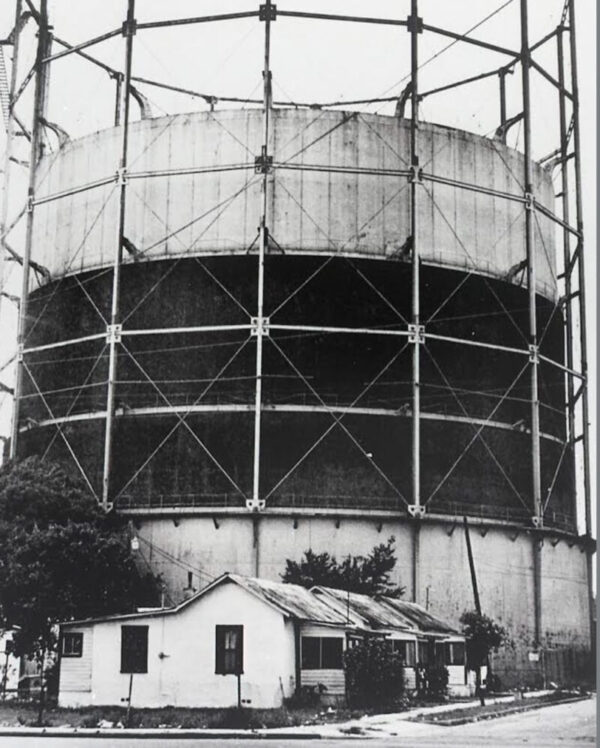

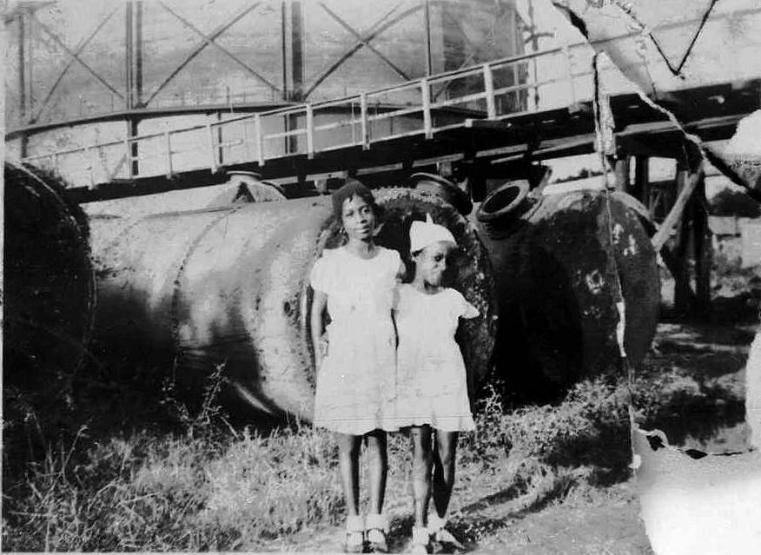

The Gas Plant District was characterized by its close-knit community and two large gas cylinders — landmarks that gave the area its name. Existing in segregated St. Petersburg, the predominantly Black neighborhood was forged out of redlining. Residents ensured that they received most of their services and found support within their neighborhood, where they felt safe.

“We knew everybody, and everybody knew us,” Lovett said. “It’s not something we just say when we say that.”

Lovett said he remembers the row of houses that were once on First Avenue South and how his neighbors would pass food to one another.

Reese said that a frequent talking point among the residents in the film was the joy of living in the Gas Plant District.

“You’ll hear about the barbecues,” Reese said. “You’ll hear about the fish fries. You’ll hear about the neighbors and how safe it was for us. St. Petersburg Times [now Tampa Bay Time]… every time they wrote about it, it was this blighted community, but we were not blighted.”

Reese noted that there were “slum areas owned by white slumlords,” but that there were also two-story and ranch-style homes, along with bungalows.

“It was thriving with about 30 businesses, about nine churches [and] 200-plus residences,” she said.

The displacement of the Gas Plant District happened over the span of approximately 20 years.

In 1978, soon after the I-175 highway extension was implemented, slicing the Gas Plant District in half, the city of St. Petersburg passed a resolution declaring the Gas Plant District a redevelopment era.

The city’s intention was to revitalize the “slum” they considered the Gas Plant District. They promised an industrial park and over 600 new jobs and affordable housing.

In compliance with the resolution, the city sought “to acquire 185 parcels of land; demolish 262 structures; relocate 27 small businesses, 45 owner-occupants, and 281 tenant households,” according to a St. Petersburg Times article written in 1979.

Between 1982 and 1983, the city’s discussions switched from building an industrial park, new jobs and affordable housing to building a stadium and acquiring a major league baseball team.

In 1984, the Gas Plant District’s landmarks, the gas cylinders, were dismantled.

In 1986, without going to referendum, St. Petersburg approved the stadium before the city was officially awarded a major league baseball franchise. That same year the city began to acquire property to construct what was known then as the Florida Suncoast Dome.

Later in 1990, eight years before the city received their baseball team, the stadium was complete, and the Gas Plant District was gone.

According to a structural racism study conducted by the city of St. Petersburg and the University of South Florida, the redevelopment displaced “2,100 Black families, businesses and

institutions from their homes.”

Julie Armstrong, a civil rights and southern literature professor at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, said the city failed to uphold its promises to residents.

“When the Gas Plant was raised, residents were promised jobs,” Armstrong said. “What they got was their community disrespected and fractured.”

Lovett and his family were one of the last households to leave the Gas Plant District. While displaced property owners received compensation, Lovett’s family, as renters, got nothing when their home was taken. With nowhere to go, they became homeless.

“For me, it was my history, but it was just lost,” Lovett said. “Now I feel like I’ve gained some of that back. I gained community. I gained my folks, as we would say, I gained my people back.”

Watching the rough cut of the documentary, Reese said that people cried. “But I was smiling,” she said. “Because finally, people could tell their stories in their words and their stories will be heard.”

Due to an overwhelming demand and a growing waitlist for tickets, an encore screening of the film was scheduled for Sunday, Feb 23. Like the premiere, the event included a panel discussion featuring filmmakers, former Gas Plant residents and historians.

Armstrong affirms that “marking the history is far better than erasing it,” though she said she wishes to see more meaningful efforts being made to address the city’s history of structural racism.

“We just want these stories to be out there,” Segall said. “We want them to be heard. We want folks to know that what happened to them not only mattered but is known by the larger community. Because it does matter that there were people here before Tropicana Field.”

Regarding the hours of extra footage, the “Razed” directors have ideas. “The cutting room floor is not the garbage,” Segall said. “We have so much valuable footage… they deserve a place to live in our community permanently.”

There are no standing monuments of the Gas Plant District. As an interviewee in “Razed” stated, the area is now “85-acres of asphalt.” But for former Gas Plant residents like Lovett, remembering what once was is not just cause for grief.

“That fills me with pride, that I came from a place and a people that could thrive in the midst of racism and depression,” Lovett said. “I’m here. This is the monument. I’m the monument.”